A medieval bear with lead poisoning: the earliest evidence of metal pollution

Researchers have demonstrated that a thousand-year-old brown bear suffered from lead poisoning. The bear lived in southwestern Romania, a region known for mining and metallurgy since the Middle Ages. This discovery represents the earliest evidence of human-caused heavy metal pollution affecting a wild animal.

The Balkan and Carpathian regions contain the oldest known mining and metallurgy sites in Europe. “We know that significant metal pollution occurred in the Balkans as early as 600 BCE, but its impact on wildlife had never been studied before,” explains Sébastien Olive, a researcher at the Institute of Natural Sciences and co-author of the study.

Among the metals extracted was lead, used for manufacturing pots, coins, weights, pipelines, and bullets. Extracting a heavy metal like lead contaminates the environment — it enters water and air, and certain plants can accumulate lead in the parts consumed by animals and humans.

Lead in the Dentine

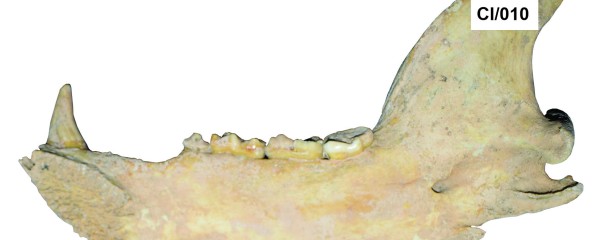

In a new study published in the journal Environmental Pollution the researchers show that a bear that lived a thousand years ago in southwestern Romania suffered from lead poisoning at the time of its death. The jawbone was discovered in 2011 in a cave in Cracul de la Cioaca Goală and was dated using the carbon-14 method.

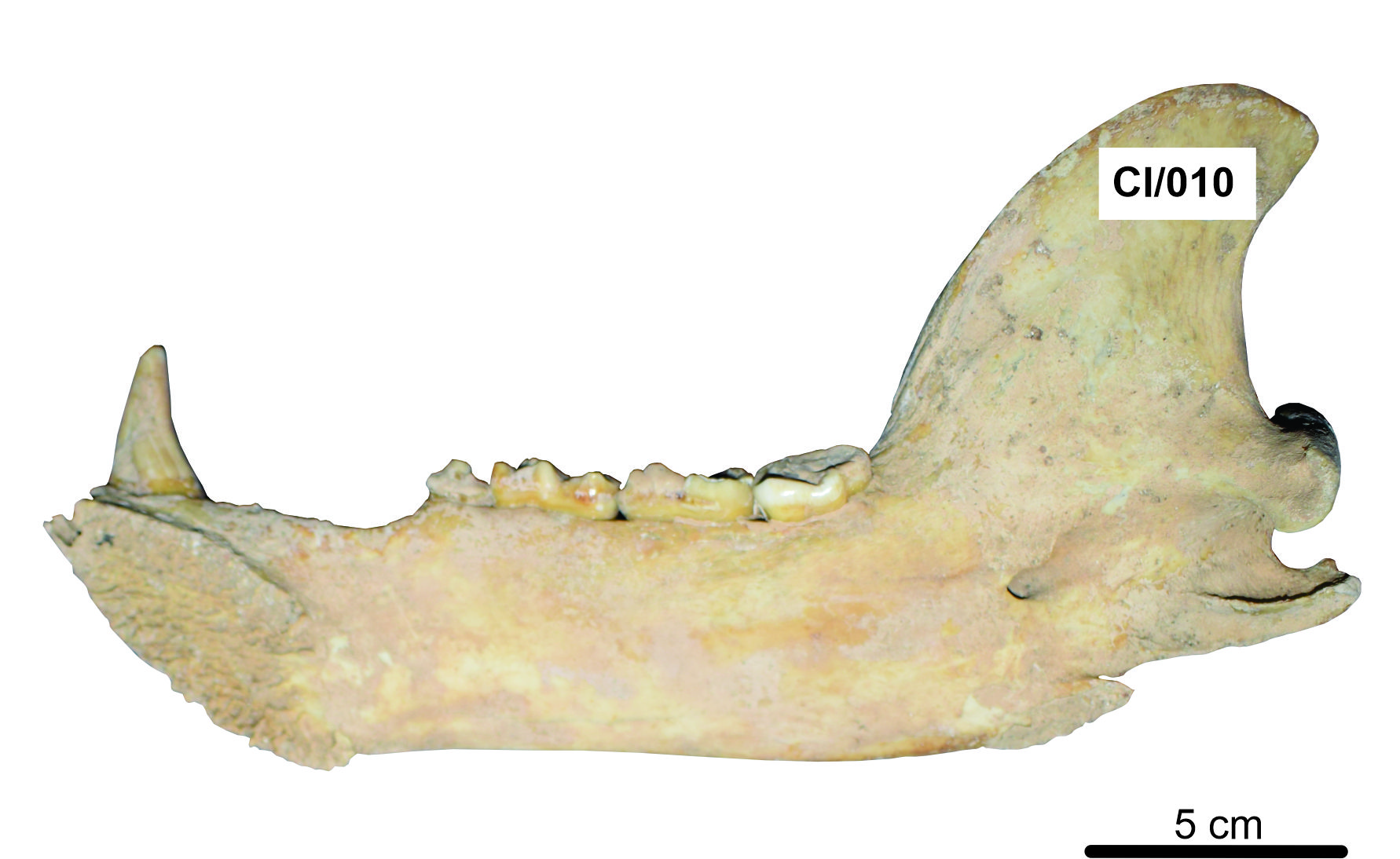

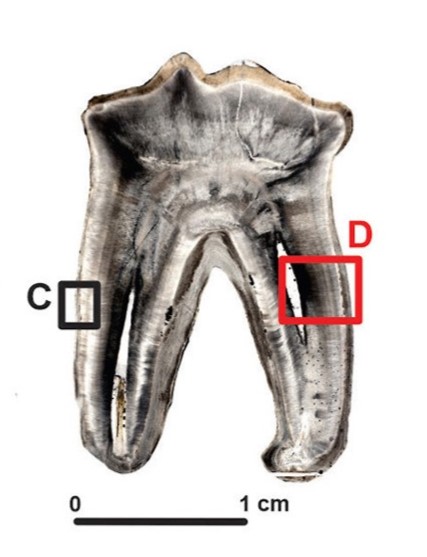

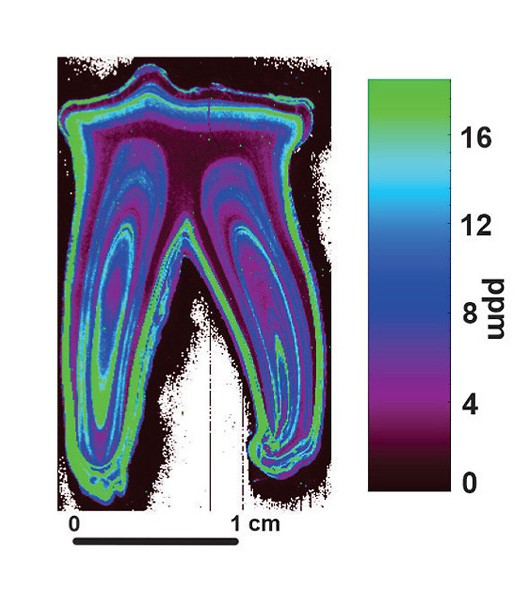

Using a laser technique (Laser Ablation Microanalysis), the researchers were able to precisely analyze the chemical composition of the dentine. A pattern emerged: lower lead absorption during winter hibernation and higher absorption during active seasons. And during its last summer, it ingested a very high dose.

It remains uncertain whether the bear died directly from lead poisoning. What is known is that it fell into a natural pit and was unable to escape. Sébastien Olive states: “The poisoning could have been the reason the bear fell into the pit. The lead concentration in its body during its last active summer reached as high as 15.2 ppm (parts per million). This level of lead pollution undoubtedly had negative effects on the bear’s health and brain.” For comparison, in humans, neurological effects occur at just 5 ppm.

Not an Isolated Case?

“This is the earliest known case of a wild animal suffering from heavy metal poisoning due to human activity,” says Olive. “It is possible that metal pollution had a broader impact on wildlife in medieval Europe, alongside hunting and changes in their habitat.”