Marine Strategy for a sustainable and resilient North Sea

A team of researchers has extensively evaluated the state of the marine environment in our Belgian North Sea. The insights have been brought together in the revised Belgian Marine Strategy. It also underlines the need for measures to ensure the ecological health and economic sustainability of the area.

The Belgian North Sea is one of the most intensively used seas in the world. With a coastline of 67 kilometres and a surface area of only 3454 km², it is home to a surprisingly rich biodiversity and numerous economic activities such as shipping, fishing, offshore energy, sand extraction and tourism. However, the marine ecosystem is under pressure from pollution, climate change and overexploitation of natural resources.

The Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) obliges all EU Member States to develop a marine strategy with the aim of achieving a Good Environmental Status. Every six years, a status report is submitted to the European Commission. In Good Environmental Status, the sea is healthy, clean and productive, and the negative effects of human activities are minimised.

“With the revision of the Belgian Marine Strategy, we are taking an important step in the protection and sustainable management of the North Sea,” says Minister of Justice and the North Sea Annelies Verlinden. “Through a combination of scientifically based policy, strict regulations and international cooperation, we are striving for a resilient marine ecosystem that benefits not only our living environment but also our economy.”

Key findings of the report

The Belgian Marine Strategy 2024 provides an overview of the current state of the Belgian North Sea in all its facets. The most striking findings can be summarized as follows:

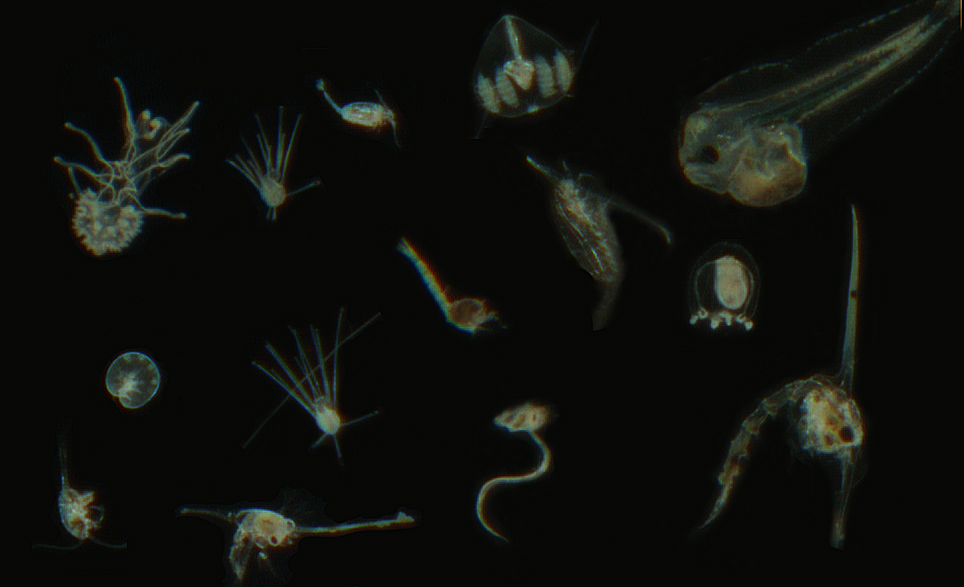

Biodiversity and ecosystem health – Populations of harbour porpoises, seabirds and other marine species, including certain fish species, remain vulnerable to human disturbance and climate change. In addition, seabed disturbance is causing habitat loss and the decline of associated fauna. Excessive inputs of nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), largely via rivers, continue to lead to seasonal algal blooms, disrupting ecosystems. New invasive alien species continue to be discovered. However, there are also positive developments. For example, the expansion of marine protected areas is contributing to the conservation and restoration of marine ecosystems.

Chemical pollution – Although the concentrations of many pollutants are decreasing, mercury, tributyltin, PAHs and PCBs, among others, remain a serious threat to the marine ecosystem. Although oil pollution has decreased to the point that it hardly occurs anymore, the risk of accidents that can lead to oil pollution remains high due to the increasing shipping traffic. The construction of new infrastructure at sea (such as wind farms) is therefore a point of concern, partly because it leads to more shipping. Ship discharges of harmful substances other than oil are not decreasing and remain a point of attention.

Climate change and ocean acidification – Average sea temperatures continue to rise, impacting marine ecosystems and species distribution. In addition, the absorption of the greenhouse gas CO₂, whose global emissions are still increasing, is leading to ocean acidification. This endangers the growth and survival of calcifying organisms, such as shellfish and plankton. Extreme weather events and rising sea levels also increase the vulnerability of coastal areas and their ecosystems.

Marine litter and underwater noise – The amount of plastic waste in the North Sea remains a persistent problem, with potentially major consequences for marine animals and coastal ecosystems. In addition, underwater noise from shipping and industrial activities poses an increasing risk to marine mammals, such as harbour porpoises.

Sustainable use of marine resources – Although fisheries management has improved, overfishing remains a challenge for certain commercial fish species. The socio-economic analysis that is also part of the revised Belgian marine strategy underlines the need for sustainable exploitation of marine resources to balance economic growth and environmental protection. In addition, offshore wind energy is expanding rapidly and plays an important role in the energy transition, but this also has ecological impacts that need to be closely monitored.

Measures and policy objectives

A sustainable future for the North Sea requires a comprehensive approach with targeted measures to address the challenges. The expansion and better protection of marine protected areas, combined with strict regulation of human activities in ecologically vulnerable zones, is essential. In addition, tackling chemical pollution and plastic waste remains a priority. Here too, stricter regulation can play a role, together with innovative waste management strategies.

Underwater noise management also deserves attention, with new technologies and policies to limit noise pollution from shipping and the offshore industry. Sustainable fishing practices remain crucial, not only through catch quotas but also through spatial restrictions that help protect fish stocks. Furthermore, strengthening climate adaptation and mitigation is necessary, with research into the impact of climate change and measures to limit its consequences.

Finally, structural research and monitoring remain of great importance for all aspects covered in the Belgian implementation of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. This is the only way to ensure that policy measures are permanently aligned with the most recent scientific insights and that environmental standards can be set for new forms of human-induced disruption, such as new infrastructure and new pollutants.

Collaboration pays off

Because marine ecosystems, the distribution of species and the influence of human factors extend beyond the boundaries of national competences, the protection and sustainable management of the North Sea requires an integrated and cross-border approach. Belgium also works closely with its neighbouring countries for this purpose, not only in terms of policy (formulating objectives and measures) but also for defining the Good Environmental Status and evaluating the current situation in relation to the environmental objectives set. The new report therefore not only used national evaluations, but also relied on evaluations carried out in an international context, such as the OSPAR Quality Status Report and the assessments of fish stocks by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES).

Successful marine management also depends on policies implemented in other areas. For example, reducing the ever-increasing emission of greenhouse gases is crucial to halting the negative effects of climate change on the marine environment. The problem of excessive nutrient inputs via rivers cannot be solved without proper coordination with nitrogen policy on land, and therefore also with agricultural policy. Furthermore, the Common Fisheries Policy is also of great importance, not only for the sustainable management of commercially exploited species (fish, shellfish and crustaceans) but also for protecting the seabed from bottom-disturbing fishing.

In addition, the public sector plays a crucial role: policymakers, scientists, companies and citizens are encouraged to contribute to the protection of our North Sea. Initiatives such as public-private partnerships and educational campaigns will play an increasingly important role in raising environmental awareness.

For more information and the full report (available in Dutch and French), visit the Belgian MSFD website.

The Department for the Marine Environment (Directorate-General for the Environment) of the Federal Public Service Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment coordinates the implementation of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive for Belgium. The Institute of Natural Sciences (scientific service MUMM) is responsible for coordinating the monitoring and assessment of the status, and works closely with various government services and research institutions: the Flanders Research Institute for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (ILVO), the Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ) and the Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain (FASFC). The Continental Shelf Service of the Federal Public Service Economy and the Marine Biology Research Group of Ghent University, among others, also provided data for the assessment.