Origin and Spread of Malaria: St. Rombout’s Cemetery in Mechelen Plays Key Role in International Research

The St. Rombout’s Cemetery in Mechelen plays an important role in an international study on the history of malaria. The study is published in the prestigious journal Nature. "The discoveries at the cemetery show how military activities and troop movements significantly contributed to the regional spread of malaria."

In a large-scale study led by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, in which the Institute of Natural Sciences also participated, researchers reconstructed the evolutionary history and global spread of malaria over the past 5,500 years. This ambitious project examined how trade, war, and colonialism contributed to the spread of one of the deadliest infectious diseases in human history.

Troops from the South

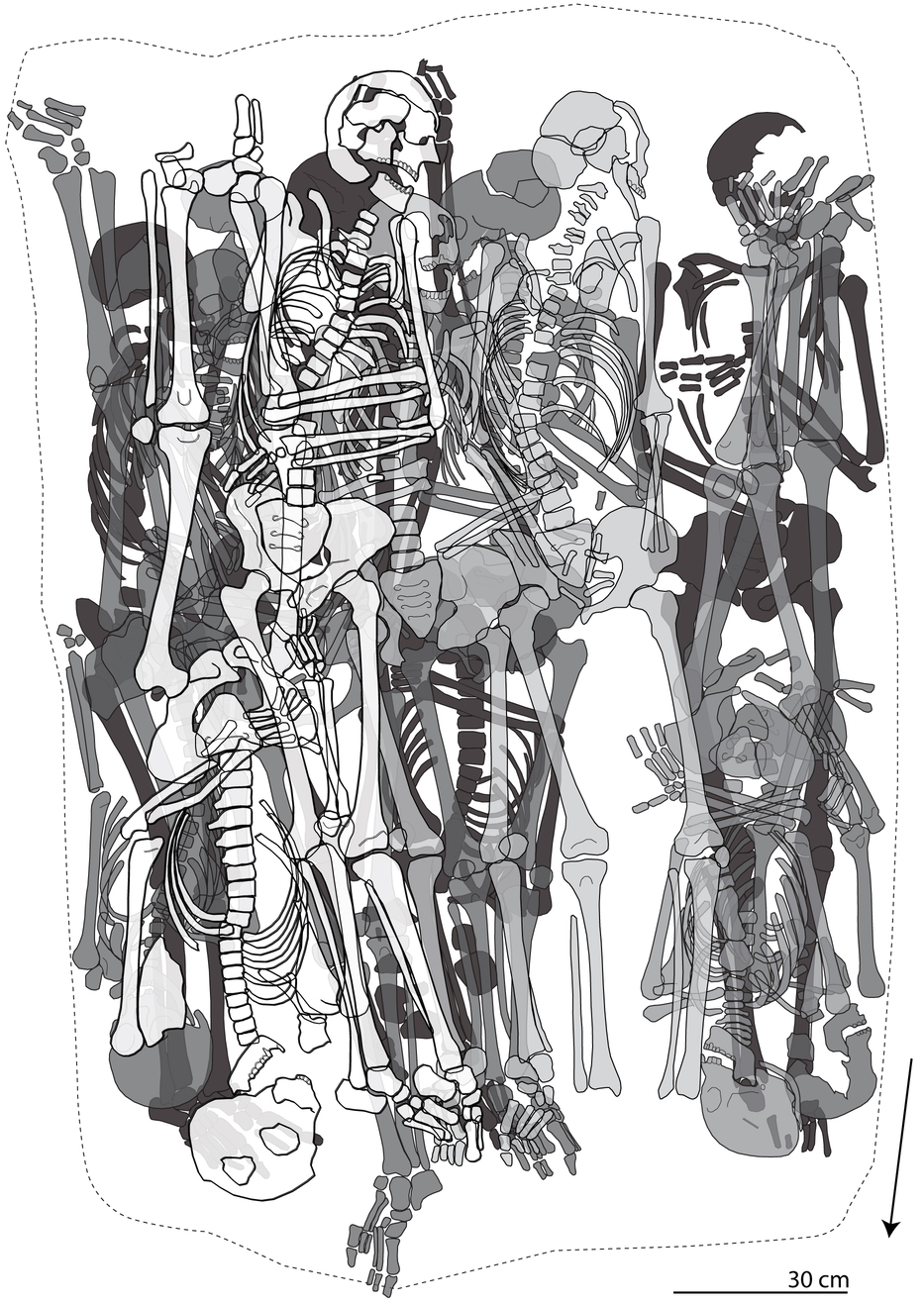

An important part of this study focused on the St. Rombout’s Cemetery in Mechelen, adjacent to Europe's first permanent military hospital (1567-1715). This site yielded more than 4,000 skeletons from the 10th to the 18th centuries. Katrien Van de Vijver, an anthropologist at the Institute of Natural Sciences, has been researching the site for years. "From the 15th century onwards, we see more multiple graves (graves where several individuals were buried at the same time, ed.) and more, mostly young, men, which suggests that the cemetery was also used for the deceased from the military hospital at that time," says Van de Vijver. "During that time, many young men from Southern Europe were recruited for the Army of Flanders of the Spanish Netherlands."

Van de Vijver was responsible for the sample collections from the cemetery for the malaria research. "Teeth are especially interesting because DNA from pathogens can still be preserved in the root canal," she explains. DNA analyses confirmed the presence of malaria in 10 of the 40 individuals examined. "Between the 12th and 14th centuries, before the military hospital existed, we found two cases of Plasmodium vivax, a type of malaria that can survive in a temperate and colder climate," says Van de Vijver. "From the 15th to the 16th century, we found eight cases of malaria: two of the Plasmodium vivax type and six of the more virulent and southern variant, Plasmodium falciparum." The researchers also examined the possible origin of the individuals using population genetics. "What stood out is that we found this southern variant in non-local men, where genetic analysis suggests an origin in the Mediterranean area. This means that it was probably brought by the troops from the south."

The military hospital, with 330 beds and up to 2,000 patients per year, played a crucial role in this transformation. "Plasmodium falciparum thrives in Mediterranean or tropical climates and was not common in Northwest Europe at that time," says Van de Vijver. "The presence of this variant among possible soldiers thus shows that troop movements played an important role in the spread of malaria."

From America to the Himalayas

In addition to Europe, the study also examined ancient cases of malaria on other continents. In America, an infected individual from Laguna de los Cóndores in Peru showed that European settlers likely introduced Plasmodium vivax shortly after first contact. In the Himalayas, the earliest known case of Plasmodium falciparum was identified in Chokhopani, Nepal, around 800 BC, suggesting that trade routes played a role in the spread to this remote region.

A Window on the Past and Future

This study highlights the dynamic nature of malaria throughout history. Advances in mosquito control and public health have reduced the number of deaths, but resistant parasites and climate change pose new threats. The researchers hope that the analysis of ancient DNA will provide valuable insights for the fight against this ongoing public health challenge.

“For the first time, we are able to explore the ancient diversity of parasites from regions like Europe, where malaria is now eradicated,” says senior author Johannes Krause, Director of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “We see how mobility and population displacement spread malaria in the past, just as modern globalization makes malaria-free countries and regions vulnerable to reintroduction today. We hope that studying ancient diseases like malaria will provide a new window into understanding these organisms that continue to shape the world we live in today.”

Katrien Van de Vijver concludes: "This study shows that humans have played a significant role in the spread of malaria throughout history and highlights the importance of historical sites like the St. Rombout’s Cemetery in understanding the spread of diseases in the past."

The study is published in the journal Nature.

Article based on a press release from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.