Our 250 Years of Natural Sciences

From a curiosity cabinet to the Museum

The Nassau Hotel (Street View above) housed the forerunner of the Museum from 1751 to 1891, almost without a break. In 1751, Charles of Lorraine endows his court with a collection of natural history: 300 square metres of glass cases and drawers house minerals, animals, plants, books, works of art and curios. But Charles dies crippled with debts; the collection is sold. In 1797 what survives becomes the Museum of the Central School and opens to the public in 1814. In 1846 the young Belgian State buys up the entire collection; the Museum is born.

The Russian Collection

A lot of 808 minerals and rocks (such as this almandine garnet, 38cm long) makes up the oldest entry in the catalogue. The collection was deposited, in 1828, at the Brussels Museum, fore-runner of our Museum, by Prince William II of The Netherlands. It had been given to him on a trip to Russia; his wife was the sister of Tsar Alexander I. These were the first pieces of our geological collection, which today contains more than 5,000 Belgian and 25,000 foreign pieces (or 80% of the types known worldwide). It includes tens of thousands of twin crystals, 500 cut stones, nearly 140 meteorites (four of which fell in Belgium), wonderful fluorescent minerals and even a very rare sample of lunar rock.

The Stone of Chaleux

This stone was found in 1865 in the Trou de Chaleux, in Hulsonniaux in the province of Namur, by the geologist Édouard Dupont, who was director of the Museum from 1868 to 1909.

The stone of Chaleux is the most famous artistic representation of Belgian fauna from the Upper Palaeolithic. Both sides of this slab of psammite (sandstone with mica) are engraved.

One side shows a horse, with a caprid (or possibly another horse) above it, and what is probably another caprid lying next to it.

On the other side is a reindeer, partially superimposed over a walking auroch.

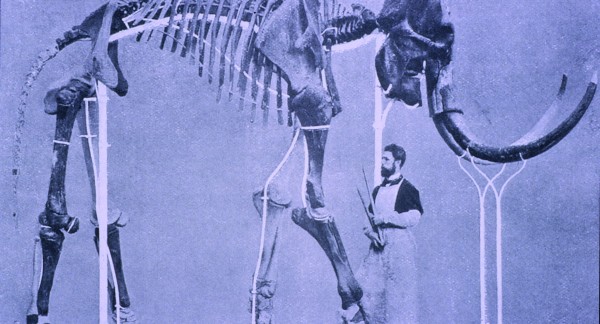

The Lier Mammoth

While work was being done on the Nete River in Lier (in the province of Antwerp) in 1860, the bones of two adult mammoths, one young mammoth, a cave hyena, a horse, and a deer were discovered. All have been dated to the Upper Palaeolithic (35,000 – 10,000 years ago). In 1869, Louis De Pauw (photo) was given the job of trying to reconstruct an adult mammoth skeleton (he would later be put in charge of assembling the Bernissart Iguanodons).

The reconstruction is exemplary. None of the bones are perforated; everything is attached to the framework with individual fixings. Louis De Pauw used carved wooden pieces to replace missing bones (like this left tusk). Visitors came from all over Europe to admire the result. At the time, the only other mounted mammoth skeleton in the world was in St Petersburg, in Russia.

This photo was taken during the disassembly of the mammoth in 2013.

Video

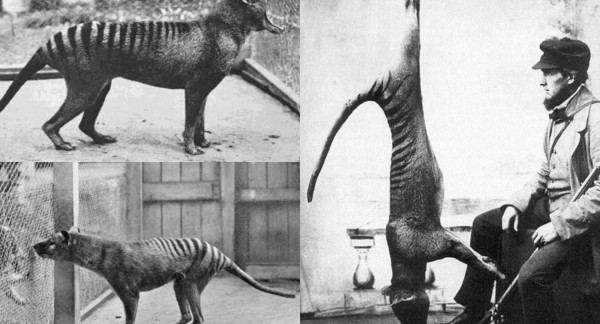

Victim of prejudice

The thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian wolf or Tasmanian tiger, is an Australian marsupial. Or at least it was: Benjamin - the last one in captivity - died in Tasmania’s Hobart Zoo on 7th September 1936.

This animal was a victim of prejudice and ignorance about its way of life. The carnivore hunted at dusk and could open its mouth very wide, making people suspect that it was a threat to sheep and so they eliminated it systematically, encouraged by bounties. Things could have been different: thylacines were easy to tame.

Left: Benjamin at Hobart Zoo in 1933

Right: iconic image taken in the late 1860s

The thylacine exhibited at the Museum has been part of our collection since 1871! It is a very rare and fragile historic specimen, so humidity and lighting have to be well adjusted. That is why the light only switches on when there is someone nearby.

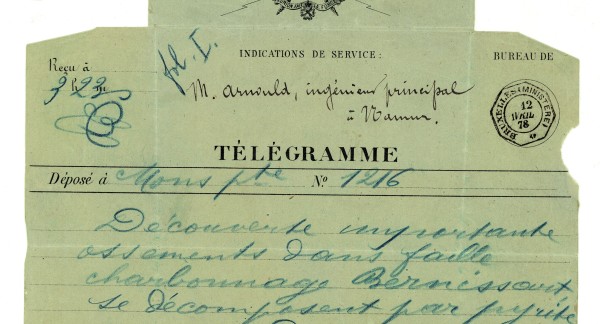

The Bernissart Iguanodons

The story starts at the end of March 1878 at the Bernissart coal mine in Sainte-Barbe. Miners were digging at 322 m when they came across a pocket of clay. Instead of going around it, they decided to go through. Several days later, they made a startling discovery: tree trunks filled with gold! What they had actually found were Iguanodon bones encrusted with pyrite (“fool’s gold”).

On 12 April 1878, the Belgian Royal Museum of Natural History (as it was then known) was informed of the discovery by telegram.

"Major discovery bones in fault Bernissart coal mine STOP Pyrite deterioration STOP Send Depauw to arrive Mons station tomorrow 8 AM STOP Will be there STOP Urgent STOP Gustave Arnaut."

About thirty relatively complete iguanodon skeletons were discovered 322m underground in a coal mine in Bernissart, Belgium from 1878 to 1881. Since the bones were still in their original position, it was possible to present the skeletons in ‘lifelike’ poses. They immediately attracted visitors from all over the world!

Today a 300 m2 glass case protects this national treasure and gives visitors an optimal view on every one of these gems. In the basement you can also see the skeletons in the position they were found in the mines and learn how they were discovered.

Did they walk on two or four legs? Did they all belong to the same species? Where did they live? Are there more in Bernissart? Find out the answers in our Google-exhibition “The Bernissart Iguanodons”.

Video

Back to the end of the 19th century

In the 1880s, the Nassau Hotel had become too small to exhibit the newly found iguanodons. The Museum was thus transferred to a building in the Park Leopold: the “Convent”, to which they added the Janlet wing, which is where the iguanodons were kept from 1902 onwards. This photo was taken during its construction in 1900, right about where today’s glass case begins.

Before hosting the Museum, the “Convent” belonged to Brussels Zoo. This zoo, created in 1851, spread through a leafy setting in what is now Leopold Park. But it went bankrupt in 1877. Despite an attempt at a re-launch it closed in 1880. The animals were sold to Antwerp Zoo, or to private menageries, even sadly killed on site. The City bought back the park; the State acquired the building for the Museum.

(Street View: the “Convent” on the right, the Janlet wing on the left)

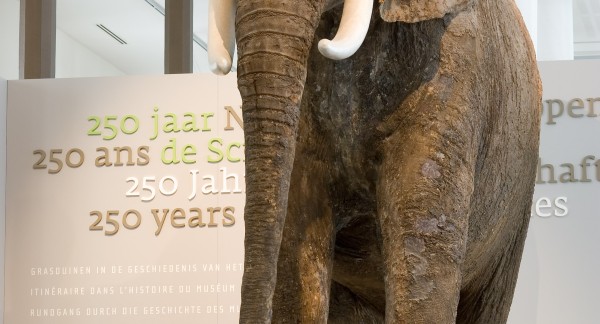

The African elephant

A specimen does not last forever. This animal, a former resident of Brussels zoo, was stuffed in 1880! Exhibiting it today necessitated restoration.

But the specimen is old and will remain so: it has its patina, its stains, its water marks. To remove all these would be to risk destroying the specimen.

Hainosaurus bernardi

It is one of the largest mosasaurs known to date. Its name means 'lizard from (the valley) of the Haine'. The Haine river also gives its name to the Hainaut province where the mosasaur was discovered, in the Ciply chalk quarries in 1884-1885.

The specimen on display is 68 to 70 million years old (Maastrichtian to Upper Cretaceous periods) and measures nearly 12.5 metres long. This authentic fossil is near complete apart from a missing section of the spinal column – replaced by fabricated bones in the exhibit – which was probably destroyed as the chalk in which the animal was resting dissolved away.

Video

The Spy Man

The first Neanderthal skeleton to be recognized as such was found in 1856 in the Neander valley near Düsseldorf, in Germany. Thirty years later, excavations led by Belgians Max Lohest, Marcel Depuydt, and Julien Fraipont uncovered two other skeletons. “Spy 2”, shown here, was one of them.

They also found prehistoric tools and the bones of extinct animals (notably cave hyenas) at the cave site in Spy, in Namur. This was the first Neanderthal find based on scientific research and not made by accident, and to have been the subject of an official report. This skeleton is made of fossil casts, “mirror-image” reproductions (for example, the right tibia, which was not found, is a symmetrical copy of the left tibia) and sculptures based on other specimens.

The Spy specimens are amongst the most recent Homo neanderthalensis: they are estimated to be 36,000 years old. Other Neanderthal remains were found in Belgium: sites at Sclayn, Fonds-de-Forêt, Goyet, La Naulette, and Engis have also yielded bones and numerous artefacts.

Video

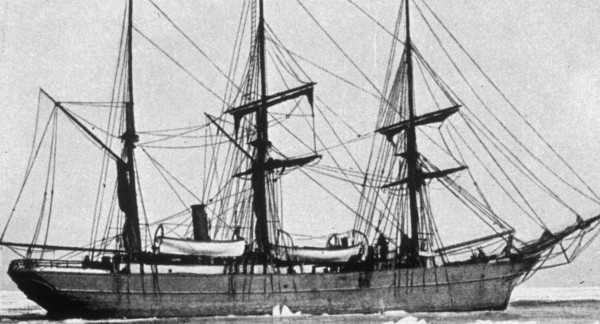

The Belgica

On 16 August 1897, the Belgica left the port of Antwerp and headed for the South Pole: initiated and led by the Belgian Adrien de Gerlache, the first international scientific expedition to Antarctica had begun.

For two years scientists carried out oceanographic and meteorological measurements, mapping the Gerlache Strait, making an inventory of the local terrestrial fauna, taking samples of marine life and collecting minerals, rare mosses, lichens, and tiny grasses. They brought back so many newly discovered species to the Museum that it took nearly fifty years to study them all!

Among the scientists on board were Amundsen (a Norwegian explorer), Arctowski (a Polish geologist / oceanographer / meteorologist), Cook (an American doctor / photographer), and Racovitza (a Romanian zoologist / botanist). Here, Emil Racovitza studying microscopic organisms in the lab of the Belgica.

The Ishango Bone

In 1950 Jean de Heinzelin, a geologist from the Museum, led excavations on the Ishango site (Congo). In the ground he discovered this 10cm long bone, which is topped with a fragment of quartz and is nearly 20,000 years old.

What makes the Ishango bone unique are the notches that appear to be grouped together. On one side, for example, there are groups of three and six (2 x 3), four and eight (2 x 4), and five and ten (2 x 5) notches.

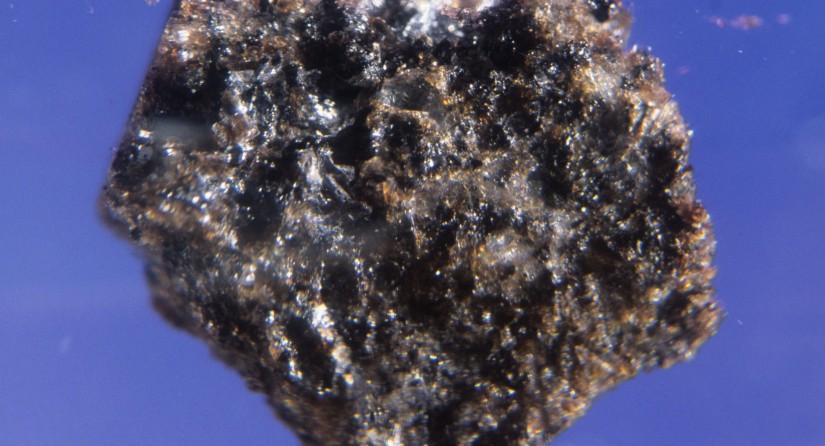

A Piece of the Moon

Apollo 17 conducted the last moon landing in December 1972. Geologist and Apollo 17 co-pilot Harrison H. Schmitt and astronaut Eugene Cernan collected more than 100kg of lunar rock, which is more than on any other Apollo misions. Schmitt was the first civilian to be included in such a flight. He and Cernan were the last human beings to have walked on the moon. This lunar rock was brought back to the earth at that time. It was donated to Belgium by US president Richard Nixon and was given to the Museum by King Baudouin in 1974. This fragment of lunar rock is barely 18mm long!

The Messel Fossils

The Messel site, near Frankfurt in Germany, was excavated by a team of our Palaeontology department in the 1980s. This extraordinary site is famous for being rich in high-quality, 47 million year-old fossils. And the diversity of these fossils is astounding: crocodiles, snakes, lizards, frogs, fishes, turtles, birds, insects, bats… and this Kopidodon macrognathus, a small arboreal (tree-living) herbivore, now extinct

Like today’s squirrels, Kopidodon macrognathus had a long, bushy tail serving as a pole for its balance as it leapt from branch to branch. Larger specimens reached 115cm; this one is a little over 70cm long.

Video

The Petrified Forest of Hoegaarden

In 2000, the construction of the high-speed rail link between Brussels and Liege laid bare hundreds of fossilized tree stumps and trunks.

They are the remains of the Glyptostroboxylon sp., a tree which is related to the bald cypresses that now grow in the swamps of Florida and Louisiana. They were found in a peat-lignite layer, which proves that the area was a swamp 55 million years ago.

Expertise Against Illegal Animal Trading

Today, many international agreements aim to protect threatened species, as well as species that could become threatened if we don’t control their exploitation or preserve their habitat. CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna) is one such agreement that aims to regulate the trade in threatened plant and animal species. The Bonn Convention, or CMS (Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals), aims to protect migratory animals. Our scientists are regularly consulted about these conventions. Their role is to inform the legislator and to identify specimens seized by customs.

Since 22 October 1987 the Siberian tiger, Panthera tigris altaica, is listed in Annex I of CITES. This annex lists the species that are in danger of extinction, and for which trade regulation is strictest. According to the WWF, there were less than 3200 of these tigers left in the wild in 2010! This specimen was confiscated and entrusted to the Museum by the Antwerp legal authorities in 2006.

In 2006, the Secretariat of the CMS entrusted our institute with preparing and negotiating an agreement for the conservation of gorillas and their natural habitat, in partnership with the Secretariat of GRASP (Great Apes Survival Partnership, a UN initiative for the conservation of great apes). The agreement was opened for signing on 26 October 2007. All ten countries where gorillas live had to sign the agreement before it could be enforced, which has now been done!

A meteorite from Antarctica

During the austral summer of 2012-2013, a Belgian-Japanese team collected no less than 425 meteorites on the Nansen Ice Field in Antarctica. Discovered on 28 January 2013, this 18-kg specimen is, according to Belgian researchers, the largest meteorite found in East Antarctica for 25 years, and the fifth largest of more than 16,000 meteorites found in this part of Antarctica.

Probably originating from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, it is an ordinary chondrite, in other words, the most abundant kind of meteorite found on Earth. However, its size makes it very special.