Face to face with a hairy beetle

Ever tried to photograph an insect sharply? Not just sharp, but so sharp that you can precisely examine the eyes, legs, and even the antennae and ultra-fine hairs? The Institute of Natural Sciences selected a few special specimens from its collection of around twenty million insects that we can view with unprecedented sharpness thanks to focus stacking.

Viewing a small insect sharply is impossible without focus stacking, a technique where multiple photos, each with slightly different focus, are combined into one super-detailed image. Focus stacking gives entomologists, the scientists who study insects, a unique insight into the world of insects, as they can literally look eye-to-eye with creatures barely a centimeter in size. This can be useful, for instance, when studying insects with very fine structures, such as wings or eyes. Moreover, photos made with focus stacking can be used to create three-dimensional models of insects. This way, digital collections are created that can be sent around the world much more easily than 'real' collections.

Jewel beetles

A lot of folks at the family gathering

The British evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane joked that if a god or divine being had created all living organisms on earth, that creator must have had an "inordinate fondness for beetles." About one in four animal species on earth is a beetle. Take the family of this leaf beetle (Chrysomelidae): it counts more than 35,000 species.

I see, I see… a fluorescent insect!

We humans don't see everything: the ultraviolet and infrared spectrum remains hidden from us. For example, rats, insects, and spiders see the ultraviolet spectrum, and some snakes see the infrared. It's interesting, therefore, to make those hidden layers visible and see what those animals see. Many specimens become fluorescent when exposed to UV light. This can indicate differences between males and females, between seemingly identical species, etc. See how UV light turns the wings of the yellow Colias euxanthe (1) purple, or those of the blue male Papilio zalmoxis (2) beautifully green. It also enhances the green color in the stick insect Neohirasea sp. (3). Details in the wings of the grasshopper Dictyophorus griseus (4) become more visible.

Colias euxanthe before and after UV-light (1).

Neohirasea sp. before and after UV-light (3).

Papilio zalmoxis before and after UV-light (2).

Dictyophorus griseus before and after UV-light (4).

Every penis is different

To distinguish insect species from one another, taxonomists also examine the genitalia. The insect penis is different for each species. Here we look at the private parts of Sogana cysana, a recently described lanternfly from Chu Yang Sin National Park in Vietnam. Insects have a Kamasutra of positions: male-on-female, female-on-male, rear-to-rear, belly-to-belly. Don't expect free-swimming spermatozoa like in mammals. Arthropods deliver a capsule-with-sperm cells, a spermatophore, into the female.

This insect doesn’t exist yet

And this one has already disappeared

Many species exist only in collections. This is the Saint Helena earwig, which was found only on the eponymous island in the Atlantic Ocean. At 8.4 cm, it was the largest earwig in the world. It may have disappeared due to habitat loss, predation by rats and mice, and invasive species.

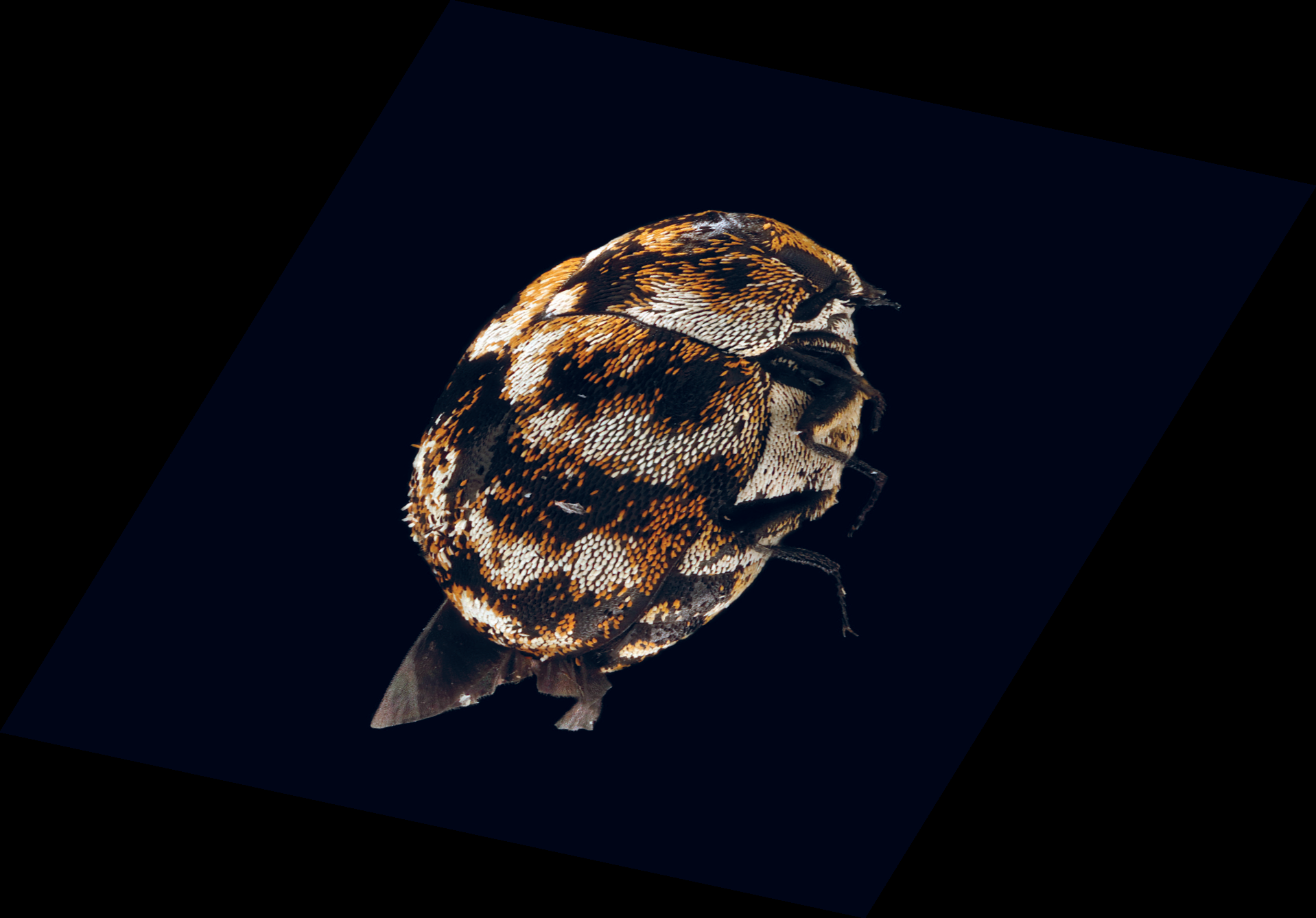

Museum beetle

This is the nightmare of every insect collector: the museum beetle. If this three to four millimeter beetle gets into boxes of carefully arranged pinned insects, the devastation is unimaginable. The larvae gorge themselves on all that delicious dead material. Therefore, boxes of prepared insects always go into the freezer room before being placed in a conservatory. The beetle also loves the skin of stuffed animals. The horror of every museum is quite a beautiful insect, with a patchwork of 'scales' on the elytra and other parts of the body.

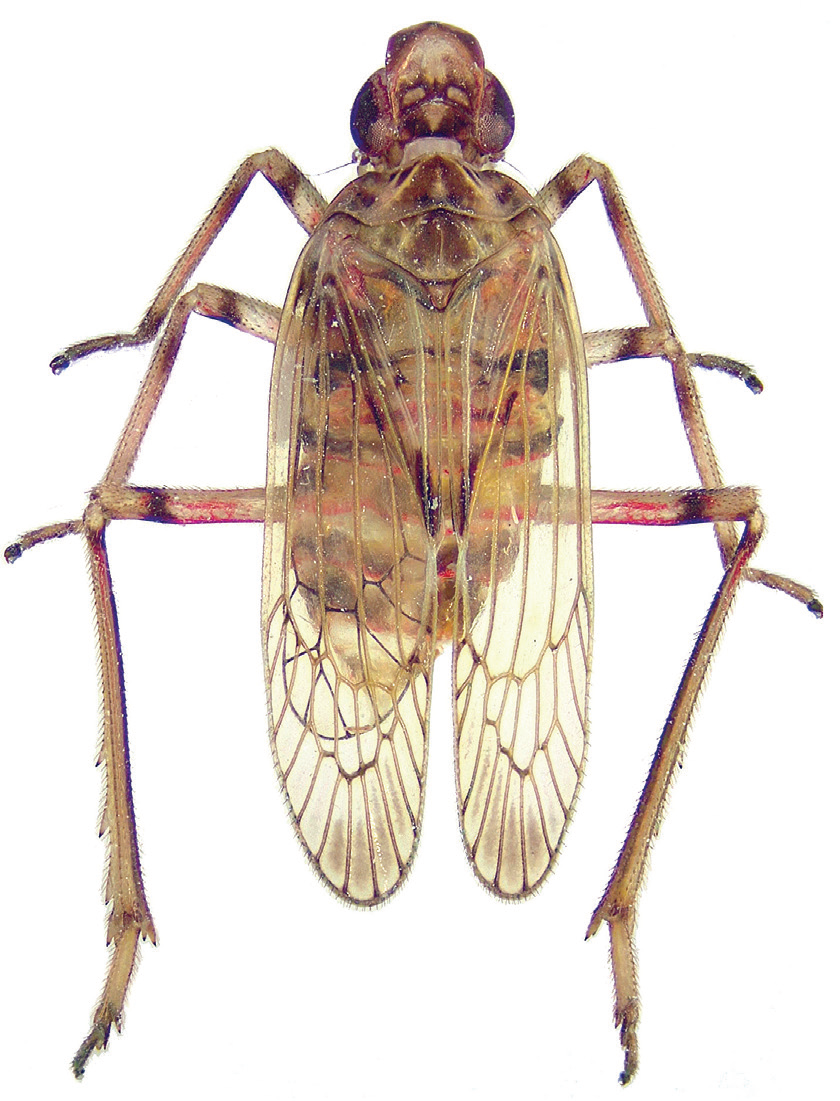

Luxury legs

One of the 7,500 species of long-legged flies. After seeing this photo, you'll never harm a fly again.

Half man, half woman

This butterfly (Cymothoe excelsa) is 'gynandromorphic' or sexually asymmetric. One half has the appearance of a male (red color), the other half that of a female (white-brown).

Butterflies captured by prisoners

Insects can also be silent witnesses to a turbulent colonial past. This is Papilio ulysses, one of the butterfly species collected by Indonesian political prisoners (mostly communists) in Boven-Digoel, a penal camp in one of the most inhospitable regions of the Dutch East Indies. The camp leader claimed to use this to instill a work ethic in the prisoners. But he was probably also influenced by magistrate and butterfly collector Emile van Delden. Van Delden donated his collection of 16,000 butterflies to the Belgian King Leopold III, who, as a prince, traveled to the Dutch East Indies three times and met Van Delden. Leopold III was an enthusiastic naturalist. Thus, the butterflies ended up in the collections of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.