The history of our collections

Our collections are at the very heart of our mission.

How did our eclectic selection of specimens grow into one of the most important in the world? And in the almost 2 centuries of our existence, what were the key societal and scientific shifts that have seen our collections take on new relevance?

On the 31st March 1846, when the statutes of the Royal Museum of Natural History were signed, the world was in a very different shape. Belgium was still a very new country, founded only sixteen years earlier. Across the country, the industrial revolution was only beginning to take hold. Our relatively small natural history collection looked very different too. It was largely based on the curiosity cabinet of Charles of Lorraine, of which few samples have been preserved to this day. Originally, natural history collections served primarily to fascinate the visitor with the beauty of natural diversity. Over the years, our society has gained an understanding of the potential held within those collections: the significance that their study can hold for our knowledge and understanding of the history of the natural world.

A very Belgian collection

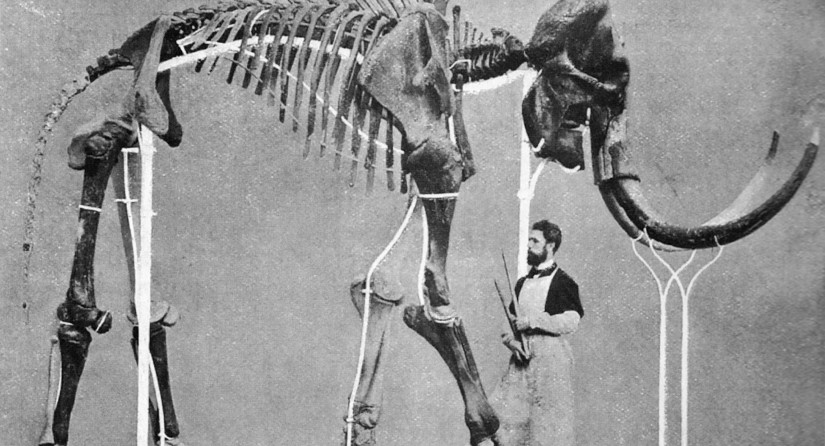

In Belgium, industrial growth helped to shape our collections through the discoveries that were made when reshaping our landscapes. Many of the discoveries that joined our collections were found thanks to large scale public works. One early example was the Lier Mammoth, discovered in 1860 while workers were digging to divert the River Nete in the province of Antwerp. The complete skeleton was an incredible addition: only the museum in St. Petersburg had such a piece at that time. The relationship between the Belgian territory and the Institute’s collection was further entrenched under the second director of the Museum, geologist Edouard Dupont. He felt strongly that the Royal Museum of Natural History must above all be "a regional museum of exploration".

A global outlook

Belgium’s links with the rest of the world also had a huge impact on the collections our Museum acquired. Belgium’s complex relationship with the Congo meant that between 1930 and 1960 our scientists collected many biological specimens from Congolese national parks. Our researchers gradually built up reference collections from expeditions across the world: the famous Belgica expeditions to the North and South Poles, the Mercator expedition in 1935 and the 1946 exploration of Lake Tanganyika to name but a few.

More recently, the significance of global cooperation among natural history collections has greatly enriched our work. Across the world, collections contain huge potential for knowledge, for example for the study and analysis of climate change. As part of the DiSSCo initiative, our collection joins this rich European research infrastructure as part of our continent’s 1.5 billion specimens across more than 130 institutions.

Advancing into a technological era

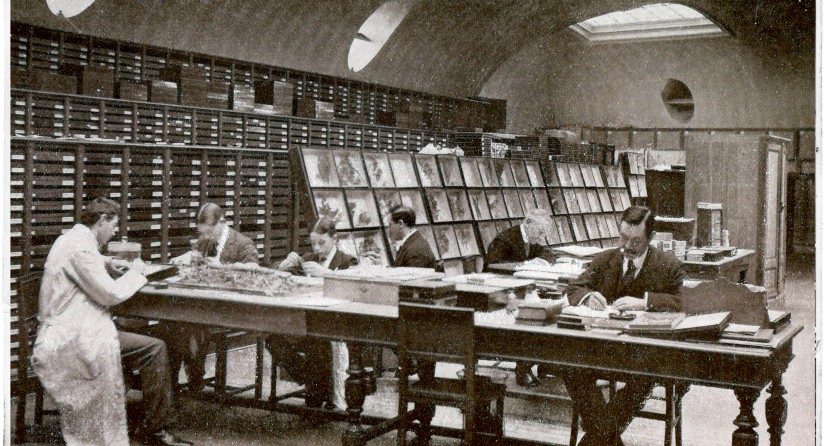

Changes in technology, too, have revolutionised our collections. Our first collection managers’ main role was taxidermy: stuffing and maintaining the specimens and only occasionally mounting skeletons. Our Bernissart iguanodons were originally exposed to the open air. It was only in 1932 that we began to treat the specimens with shellac to prevent the pyrite in the bones from oxidising and protect them in huge glass cases. With contemporary techniques we can maintain our specimens in even better condition.

New perspectives on ethical questions

While European collections have benefitted massively from links with the global south, our perspective on the ownership of these benefits has shifted. Developing countries have a wealth of genetic resources at risk of being exploited.

in 1992 the Convention of Biological Diversity was drawn up to help ensure that the benefits are shared in a fair and equitable way. Our Institute participated in negotiations of the Nagoya Protocol in Japan in 2010, setting out a legal framework for collecting and using specimens internationally. Now every specimen entering our collection needs a permit: a time-consuming process, but one which improves access to research results and ensures no country loses out.

Still today, our understanding of ethical questions around our collections continues to grow. Our anthropological collections tell a complex and sometimes disturbing story about the history of humans as part of the natural world which raises a number of moral questions for us as the Belgian institution with the greatest number of specimens of human origin in our collection. The HOME project, launched by our Institute in 2020, recommends repatriation of historical human remains from former Belgian colonies and the creation of a focal point on human remains.