Ancient Egyptians Deformed Sheep Horns

Researchers from the Institute of Natural Sciences and the University of Oxford have found the oldest evidence of livestock whose horns were deliberately deformed. The ancient Egyptians forced the corkscrew-shaped horns of sheep, which naturally grow sideways, to stand upright. “For now, it’s just speculation as to why they did it,” says archaeozoologist Wim Van Neer.

Hierakonpolis, also known as Nekhen, is an archaeological site along the Nile in Egypt, slightly south of Luxor. Long before the construction of the pyramids and the rule of the pharaohs, it was one of the largest cities and a significant political center between 3700 and 3500 BC. It is also one of the few sites with cemeteries for both ordinary people and the elite.

Oldest Zoo

In the elite cemetery, as many as 180 animals were buried alongside notables. One-fifth of these were wild animals, such as local hippos and crocodiles, as well as baboons and elephants imported from the south. Archaeologists also uncovered many cats, dogs, and livestock. Because of the abundance and variety of animals, Hierakonpolis is unique and is considered the oldest zoo.

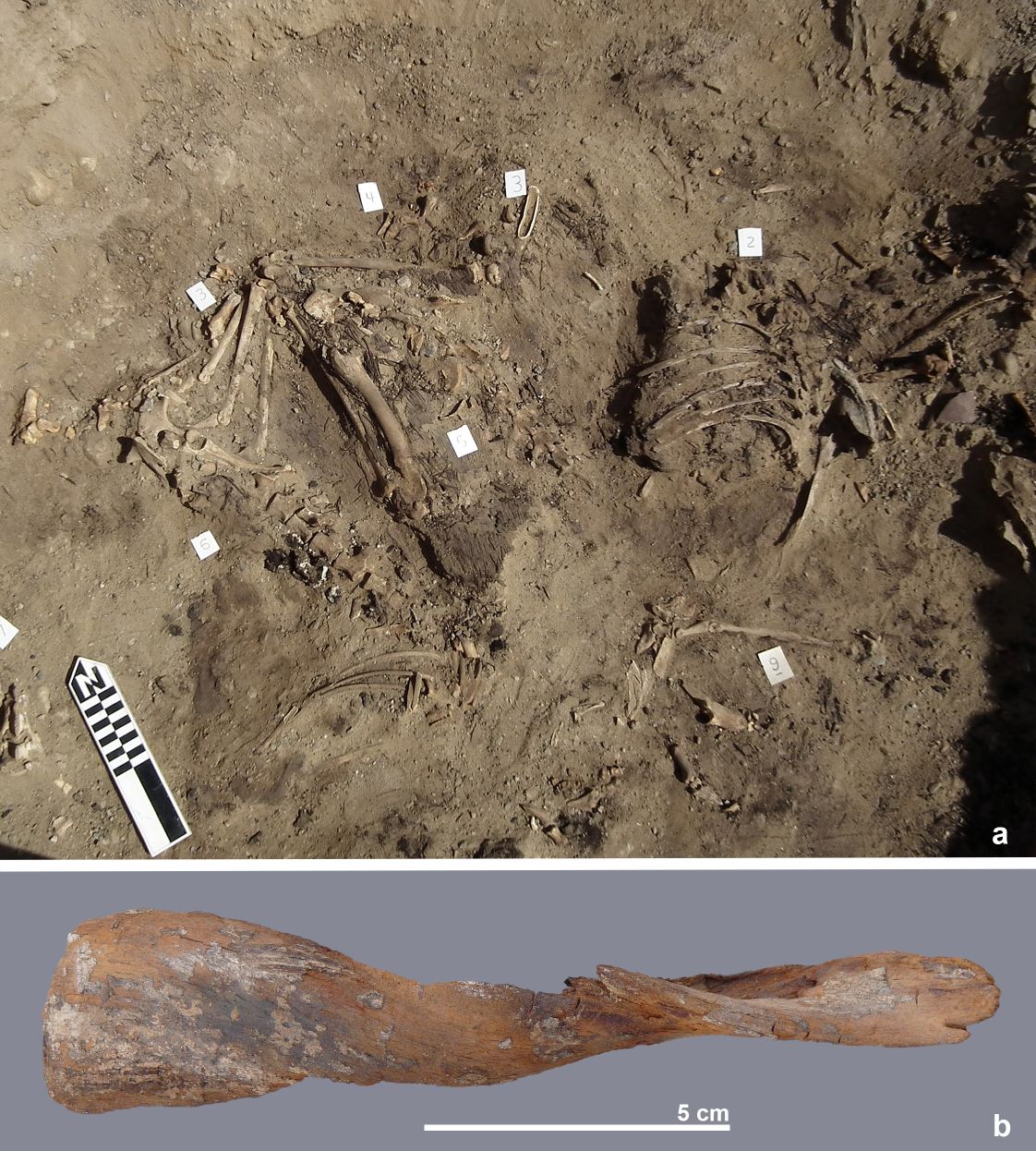

In a new study published in Journal of Archaeological Science, archaeologists Wim Van Neer, Bea De Cupere, and Renée Friedman describe six sheep found in a grave. Normally, this species has spiral horns that grow horizontally and laterally, but in three specimens, the horns were directed upwards. Another sheep had less straight horns, but they were closer together than usual. One sheep had its horns entirely removed.

Upright Horns

“Notches in the horns suggest that the ancient Egyptians used ropes to bind them together,” says archaeozoologist Bea De Cupere (Institute of Natural Sciences), who participated in six excavation campaigns at Hierakonpolis. “Holes in the skull bones indicate that herders also broke the skull of the young animals to force the horns to grow upright. It is a practice that certain African pastoral communities still apply to cattle.”

The sheep in the elite cemetery were found to be much older — 6 to 8 years old instead of the usual 3 years — and larger than their counterparts found in butchery waste elsewhere on the site. “This is the result of castration,” says De Cupere. “The sheep not only become easier to handle but also grow larger.”

Showing Off

The reason why the ancient Egyptians deformed the horns remains unclear. Archaeozoologist Wim Van Neer (who participated in twelve excavations at Hierakonpolis) says, “The elite wanted to display their power by keeping wild and exotic animals, and perhaps also by straightening the horns of impressively large sheep. Maybe they wanted the sheep to look like addaxes from the Sahara? Or perhaps the animals were involved in rituals? For now, we can only speculate.”

The researchers hope to find more livestock skulls with deformed horns to better understand this remarkable practice. The discovery at Hierakonpolis provides the oldest evidence of horn deformation in livestock — 1,000 years earlier than a site in Sudan with deformed cattle horns — and the first known case of such practice in sheep.